In the 18th century, the official religion of the Virginia colony was Anglican. However, there was a substantial and growing population of Scotch-Irish settlers of the Presbyterian faith who along with Quakers, Baptists, and Lutherans brought change to the religious culture of Virginia. Presbyterian congregations are organized into local district presbyteries that are governed under regional bodies known as synods. Hampden-Sydney College was founded under the auspices of the Hanover Presbytery in Virginia, which served under the Synod of New York and Philadelphia.

Consideration by Hanover Presbytery of the establishment of an academy south of the James River and the Blue Ridge Mountains began as early as 1771, but it was not until early 1775 that the plans were realized.

February 1, 1775: A gathering of representatives of Hanover Presbytery was held at Slate Hill, the home of Nathaniel Venable, which was located three miles south of the present-day campus, to review the results of a successful fundraising effort begun the previous year at the request of Hanover Presbytery by Presbyterian congregations primarily in Prince Edward and Cumberland Counties.

February 2, 1775: Members of the presbytery visited potential sites near Prince Edward Courthouse (now Worsham) and decided on a tract of about 100 acres offered by Peter Johnston. There they decided to build an academy building, rector’s house, and such other necessary buildings as funds allowed. At the same meeting, four ministers and eight laymen including Anglicans were elected as the Board of Trustees.

February 3, 1775: The Board elected Samuel Stanhope Smith as the rector—chief administrative officer—of the new academy and fixed the tuition at four Pounds per student.

April 20, 1775: Control having passed from Hanover Presbytery to the Board of Trustees, the Johnston land was surveyed and conveyed to the new academy. The deed was recorded on May 15, 1775.

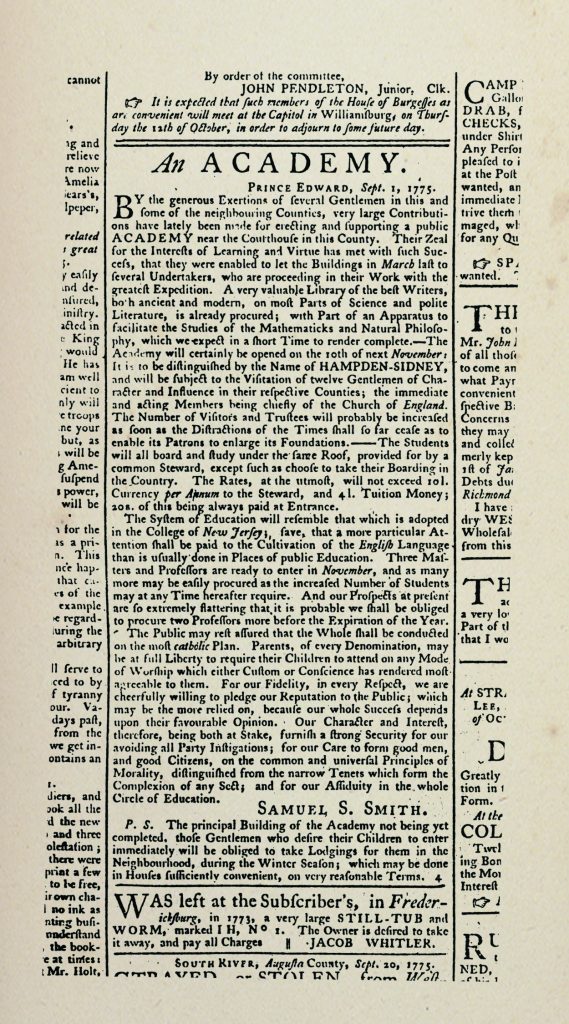

September 1, 1775: Smith advertised for students in Williamsburg’s Virginia Gazette with an anticipation of beginning classes in November. In the 18th Century, the academic year was divided into two sessions: a winter term of six months—November through April—and a summer term of four months—June through September.

Smith’s advertisement noted, however, that “the principal building of the Academy not yet being completed,” students would be “obliged to take Lodgings…in the Neighborhood.”

November 8-10, 1775: The trustees met, and a steward was chosen and requirements for food drawn up. The steward was to provide a “good and wholesome diet for students.” The steward was to provide servants, most likely enslaved individuals, to help students keep their lodgings clean. Students furnished their own beds and candles and were responsible for laundry and firewood.

We celebrate November 10 as Founder’s Day. College records of its earliest days are incomplete or have been lost. We know that on that date there were in place a Board of Trustees, a rector, three assistants (tutors/teachers), and a steward to feed students but how many students enrolled that November of 1775 is unknown. There is definitive evidence that traditional classes were held in January 1776, although it is possible that they were held before then.

The Academy Building

Construction of the main building continued to be problematic. Campus buildings were made from wood, but the main building was to be more substantial; scholars agree that the structure, begun in the summer of 1775, was not expected to be completed until summer 1776. It was constructed of bricks made and timber cut on campus and built by local craftsmen and laborers, free and enslaved.

The three story, twelve room brick structure is believed to have been the largest structure of its kind west of Williamsburg.

Almost all the original 18th Century structures had deteriorated or been demolished by 1840. The legend is that bricks and timbers from the principal academy building were used in the construction in 1833 of a house, which still stands, for President Jonathan Cushing.

Patrick Henry and James Madison

On February 2, 1775, four ministers and eight laymen were elected to serve with Samuel Stanhope Smith as the original Board of Trustees. The Board met on November 8, 1775, and elected five new members, among them were Patrick Henry and James Madison, both rightly numbered among the early trustees.

Patrick Henry was the more active during his tenure. Henry helped Hampden-Sydney secure a state charter and seal in 1783, which officially promoted the academy to a college. He lived for a time in Prince Edward County and several of his sons attended Hampden-Sydney.

Henry was famous at the time of his election to the Board. At the Virginia Convention in March of 1775, he delivered the phrase for which he is best known— “Give me liberty, or give me death!”

Madison, however, was not as well known. His fame as “The Father of the Constitution” would come years later, but through his friendship, begun as students at the College of New Jersey (later to be renamed as Princeton University), with Samuel Stanhope Smith, his thinking influenced the ideals of the new academy.

Henry and Madison are the notable names here, but it was Samuel Stanhope Smith, a 24-year-old native Pennsylvanian and a 1769 graduate of the College of New Jersey, who pulled it all together. Smith offered to lead the new academy, was elected first head, traveled north to purchase books and scientific equipment and to recruit faculty, and determined a curriculum of general education. Smith was dedicated to the religious and moral education of his students. and established the mission – “to form good men, and good citizens.” He was also a slaveowner who, paradoxically, theorized about the “unity of mankind.”

The Origins of the Name

It is believed that the name Hampden-Sydney was proposed to Smith by John Witherspoon, president of the College of New Jersey, with whom Smith had studied theology and philosophy. Smith visited Witherspoon in the summer of 1775 and married Witherspoon’s daughter, Ann.

Witherspoon chose the name Hampden-Sydney to symbolize devotion to the principles of representative government and full civil and religious freedom which John Hampden (1594-1643) and Algernon Sydney (1622-1683) had outspokenly supported, and for which they had given their lives in England’s two great constitutional crises of the 17th Century.

John Hampden and Algernon Sidney

History for most colonial Americans was the history of Great Britain. From that history were drawn John Hampden and Algernon Sidney. For leaders of the revolutionary movement in America, including Witherspoon, Madison, and Henry, these men represented the admirable defense of political freedom against tyrannical governments. Hampden is seen by some scholars as the first Englishman to object to taxation without representation, which became a major rallying point for the colonists by the 1760s and 1770s. While the only Virginia college that existed at this time, William and Mary, was named for monarchs, the decision to name Hampden-Sydney after two men seen as inspiration for revolutionary ideas is notable.

John Hampden was a Puritan, landowner, and Parliamentary leader famous for his opposition to King Charles I over a form of royal taxation known as ship money. The tax controversy contributed to the precipitation of the English Civil Wars of 1642-1651. Hampden subsequently fought against the monarchy and died of injuries sustained at the Battle of Chalgrove Field in 1643.

Algernon Sidney was an English politician, republican political theorist and colonel. He was arrested as an accomplice in an attempt to assassinate King Charles II and, after being tried and convicted, he was beheaded in 1683. At his trial, passages from the manuscript of his Discourses Concerning Government were introduced as evidence that he believed in the right of revolution. The treatise later became a key text for revolutionaries in the North American colonies.

The Commemoration of 1876

Ten years after the end of the Civil War, Virginia still struggled with the social and economic impact of the conflict. Agriculture had been slow to recover. The Financial Panic of 1873 triggered a great depression in the United States and at least 100 banks failed nationwide. With no funds for a celebration in 1875, the Board declared Hampden-Sydney’s founding date to be 1776, neatly aligning with that of the Nation. Although the Centennial celebration was a modest affair, it did take place in June 1876. Afterward, the designation of 1776 as the founding year remained in place. The change was a matter of finances and demonstrates that history can at times be subject to rewriting for the sake of convenience.