We know that ethanol exposure during development has many negative consequences for the offspring. This summer I’ve been working with Dr. Erin Clabough investigating mouse brain morphology following a one-time ethanol intoxication event in the early postnatal period for mice (which is equivalent to the third trimester of a human pregnancy). We have harvested mouse brains, followed a Golgi impregnation procedure, sectioned brains using a cryostat, followed staining procedures, used microscopes and computer programs to identify and trace medium spiny neurons, and will in the future analyze the number and types of dendritic spines.

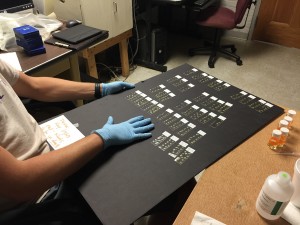

Jamie Ingersoll ’18 undertaking a Golgi staining process on mouse brain sections. The Golgi stain impregnates approximately 10% of neurons with a black pigment. We lost some usable brain sections into the wash, but in most sections, we were able to see the outline of individual neurons under the scope.

In prior study done in Dr. Clabough’s lab, we found increased branching in individual neurons in the striatum of the mouse brains immediately following a developmental ethanol exposure—which is the opposite of what we thought we’d find. We are now investigating different stages of mouse development to see when this branching phenotype disappears.

The most difficult parts of research so far have been when we were sectioning on the cryostat and it fought us for what seemed like years never wanting to yield a usable section and also the staining process where we had to watch as brain after brain slid off the slides into the unusable wash left behind.

This experience has showed me a whole new level of patience and also how important it is to not rush the process—for example, when something like the cryostat decides it will finally cooperate, then prepare to stay for a while and crank because the next day it may not be so kind. But the best part is when everything works and we are able to see and interpret results.

We will present our research at the 2016 Society for Neuroscience meeting in San Diego in November. We hope that our research will provide insights into not just how just one binge of ethanol can affect neurons in the brain, but also how medium spiny neurons are involved in the response to ethanol and how that response may change throughout development.