This summer I have had the privilege to join Dr. Clabough and a collaboration of people working on a project called Turtle Sense, which involves placing sensors in turtle nest to monitor when turtle hatchlings will emerge. The physical placement of an egg-shaped sensor into a turtle nest enables the relay of motion data in the nest back to a communication tower and then to a database. The motion data can then be used to predict baby turtle emergence.

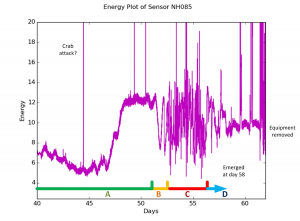

Turtle Sense data from previous years have shown that these sensors are capable of predicting when sea turtles will actually emerge from their nest within a few days. Our method of data collection can divide the motion of a sea turtle nest from day 0-60 into four phases. Phase A consist of a quiet incubation period (roughly 50 days). Phase B is a transition period that usually has some large swings with a frequency of 2-4 swings per a day. This phase ends with a quiet and low motion reading, which is often lower than anything in the preceding weeks. Phase C is the hatching activity, which is typically 4 days long and characterized by erratic, frequent motion. Phase D is a quiet period indicating emergence is imminent.

This summer I’ve been looking at past years’ sensor data collected at Cape Hatteras to better formulate an experimentally outlined procedure for optimizing the way data is collected, as well as how the data can be used to best create a way for other people to implement the same technology in sea turtle nests in other geographic locations. We’ve seen in some data from past years that the graphs can detect non-turtle motion periods at certain points, which may indicate predation from ghost crabs, washouts from the ocean, wind manipulating the sensors, and storms.

We are working to implement a defined protocol for what to do when a nest is found, as well as specifically how each sensor should be placed into a nest to ensure less experimental error. During full nesting season, we can expect well over 200 sea turtle nests. Nest management currently requires blocking off the nest upon discovery, and after approximately 1.5 months, a larger beach enclosure is placed around the nest that essentially blocks off people from crossing that section of the beach until the nest has clearly emerged.

The best part about this research experience is that I actually get to live in Hatteras, NC for the summer. Living down here and interacting with the locals has taught me a lot about how people view sea turtles and their nesting, as well as the differing views that people have over how the beaches should be utilized regarding sea turtle nests. The nature of the project is definitely one that has proved to be a learning experience— we no longer have control over what we’re working with because we’re actually working with live animals that follow their own life cycle.